The hype surrounding AI-based Autonomous Driving or Full Self-Driving (FSD) has, to some extent, created unrealistic expectations. The crux of the issue lies in AI’s probabilistic, non-guaranteed behavior, which fundamentally complicates the development and validation of FSD systems. The uncertainty inherent in AI-based decision-making means we are attempting to address a relatively straightforward human driving task with a methodology that is overly complex, difficult to verify, and still unproven for safety-critical use.

AI models can behave unpredictably because they rely on complex statistical patterns and approximations. Their stability depends heavily on the quality and diversity of the data they learn from. A neural network doesn’t reason logically — it infers statistical relationships between inputs and actions, so when real-world situations differ from its training data, those approximations can lead to unpredictable behavior. At present, there’s no reliable way to interpret1 or reverse-engineer a neural network to predict its actions across contexts, and testing every possible real-world scenario is impractical — leaving their behavior in dynamic conditions largely unpredictable.

Object detection—critical to FSD’s perception stack—still struggles at long range, under occlusion, with motion blur, in low light, and with unusual objects. Modern stacks add context via multi-sensor fusion (e.g., multi-camera, radar, lidar) and temporal/occupancy models, but they still don’t use context the way humans do.2. Moreover, the computational burden of these models—especially at inference on GPU/NPU hardware—can raise inference latency which is not deterministic on such architectures, limiting real-time performance. This combination of unpredictability and timing constraints can lead to unsafe maneuvers. An increasing number of AI-powered vehicles taking to the road without guardrails can make driving conditions more chaotic.

AI-based decision-making in FSD systems has demonstrated significant risks, as evidenced by several crashes and fatal accidents. In one incident, an Uber autonomous vehicle fatally struck a pedestrian because the software misclassified the pedestrian as an unknown static object. In another incident, GM Cruise‘s autonomous vehicle detected an imminent collision just 0.4 seconds before hitting a pedestrian at 19.1 mph. But 0.4 seconds wasn’t enough time to brake, and the vehicle subsequently dragged the pedestrian 20 feet before coming to a complete stop. Waymo and Woven by Toyota have also experienced crashes requiring nuanced and timely decision-making.

Tesla’s Autopilot has been involved in numerous crashes and more than a dozen fatal accidents. By contrast, robotaxis such as Waymo and Cruise have, to date, reported fewer fatal crashes than Tesla’s Autopilot or FSD, largely because they operate within limited Operational Design Domains (ODDs)—restricted map coverage, road types, speeds, and weather—and with remote human-in-the-loop assistance.

One of Tesla’s incidents involved Jeremy Banner3, whose vehicle, operating on Autopilot at nearly 69 mph, collided with a semi-truck. The impact sheared off the car’s roof, tragically resulting in Banner’s immediate death. According to Tesla, the Autopilot vision system did not consistently detect and track the truck as an object or threat as it crossed the vehicle’s path.

In July 2023, a similar crash with a semi-truck killed Pablo Teodoro, a 57-year-old bakery owner. In another fatal incident, Walter Huang4, an Apple engineer, died after his Tesla Model X, operating on Autopilot, collided with a barrier on Highway 101. Federal investigators later determined that the vehicle’s forward-collision warning and automatic emergency-braking systems failed to engage, resulting in the crash.

Pictures showing Walter Huang’s Model X accelerated into a barrier on U.S. Highway 101 in Mountain View, CA, on March 23, 2018. Courtesy of Reuters.

In a 2019 crash in Key Largo, Florida, Naibel Benavides Leon, 22, was killed and her boyfriend Dillon Angulo suffered catastrophic injuries when a Tesla Model S, operating in Autopilot mode, blew through a stop sign and struck them at over 60 mph. A later analysis of hacked vehicle logs5 reportedly showed that the car had detected the pedestrians but still plotted a path directly through them.

Although Tesla’s safety reports suggest that Autopilot has a lower accident rate, the miles-driven per incident metric is misleading. It doesn’t account for human interventions that would have prevented accidents. This metric also fails to account for the complexity of real-world driving conditions, such as adverse weather, road construction, unpredictable traffic patterns, poor road maintenance, and the presence of pedestrians and cyclists. These conditions introduce uncertainty that the report doesn’t account for, leaving insufficient evidence to conclude Autopilot’s safety. Tesla’s Autopilot and FSD Supervised are SAE Level 2—the driver remains responsible. If Autopilot’s evidence is insufficient, FSD Supervised—relying on the same vision-first, single-stack, and increasingly end-to-end neural network design—lacks demonstrated safety. Reaching true SAE Level 4/5 autonomy (FSD without human supervision) will require significantly stronger evidence and independent validation.

There is also at least one confirmed fatal crash with FSD Supervised (Rimrock, AZ, 2023). Tesla’s FSD marketing lulls drivers into a false sense of security, leading to over-reliance on technology. This over-reliance compromises driver awareness, delays responses to hazardous conditions, and can potentially lead to accidents. The fact that Tesla’s current FSD is not fully autonomous as defined by SAE levels 4/5, despite the product’s name (minus the small-print qualifier “Supervised”), allows the company to attribute failures to human oversight and reduce its legal liability.

Tesla’s current full self-driving vision strategy — relying solely on cameras and an end-to-end neural network — is fundamentally constrained6. While cameras can capture what humans see, the system lacks the contextual understanding, higher-level reasoning, and redundancy that human perception relies on. Without complementary sensors, explicit reasoning layers, and formal safety validation, the system remains bound by the unpredictability of its statistical approximations. No matter how much data or compute you throw at it, it cannot attain the safety requirements for reliable autonomy.

The issues above underscore a fundamental limitation of neural-network–based decision-making in FSD. While some unpredictability is tolerable in language models like chatGPT, it is unacceptable in driving, where small errors can be catastrophic. These systems are also difficult to debug; post-incident updates can have unintended side effects. Because neural networks are prone to catastrophic forgetting during continual learning, fixes can degrade previously learned capabilities and introduce new failure modes. Some changes may also require costly hardware upgrades to offset degraded performance. Finally, training and maintaining such models is resource-intensive—demanding large-scale compute, electricity, and extensive data curation/labeling—raising sustainability concerns.

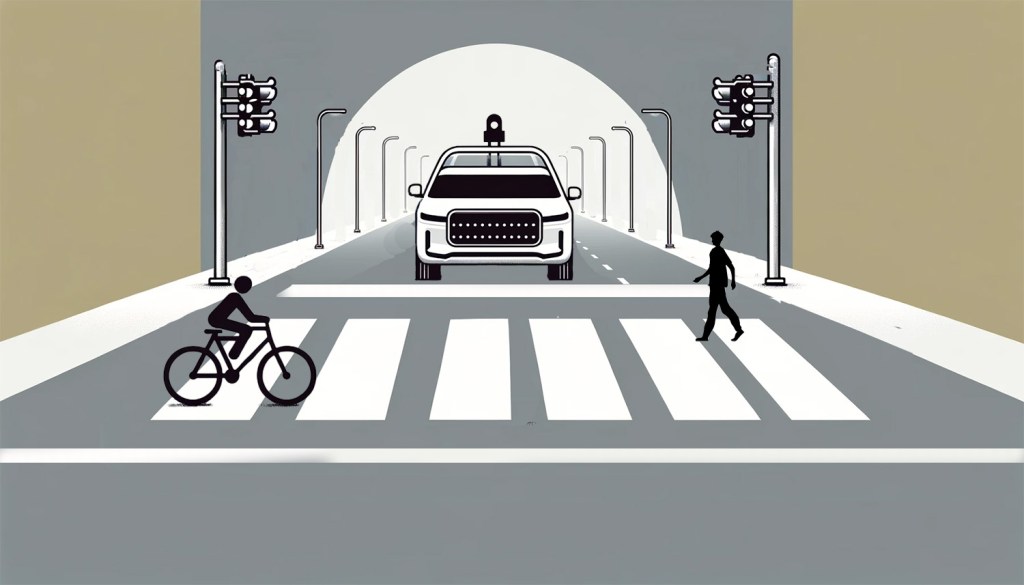

Given the shortcomings of current neural networks, the following hybrid approach would make autonomous vehicles safer. Redundant and complementary sensors using sensor fusion techniques increase the reliability of perception. Offloading time-sensitive processing to custom hardware—such as Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) and Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs)—enhances real-time obstacle response with ultra-low latency and deterministic performance. Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V), Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I), and Vehicle-to-Human (V2H) communication further strengthen resilience in unforeseen circumstances.

However, hybrid FSD architectures face higher costs and scalability issues due to their complexity. Achieving the ideal balance is essential for their adoption. To consistently achieve crash rates below human baselines, a high—potentially very high—penetration of modernized vehicles and upgraded infrastructure is likely required to enable coordinated safety improvements. That means standardized V2X communication and robust sensor suites so vehicles can coordinate with one another and with road infrastructure. Until then, the current promises around AI-centric FSD appear to be more of a PR stunt to fire up investors than a genuine step toward safe, reliable autonomous driving.

But AI-based FSD systems show real promise in controlled and domain-specific deployments—including autonomous shuttles, geo-fenced robotaxis, defense logistics, mining, and agriculture. Broad adoption, however, depends on a regulatory and assurance framework that earns public trust through clear, consistent, and enforceable safety requirements. Note that SAE J3016 defines levels of driving automation; it’s a taxonomy, not a safety standard. There is a patchwork of documents addresses parts of the problem—ISO 26262 (functional safety), ISO 21448/SOTIF (safety of intended functionality), UL 4600 (autonomy safety case), and cybersecurity/OTA rules (e.g., ISO/SAE 21434, UNECE R155/R156)—but no single standard unifies them into a coherent, enforceable framework for driverless FSD, particularly for machine-learning-centric perception and planning.

In the context of robotaxis, technological challenges may be overcome, but significant operational hurdles remain. While the primary objective is to cut costs by replacing human drivers, companies face substantial overheads: insurance and liability, regulatory compliance, passenger safety and security (including vandalism prevention and incident response), vehicle cleaning, lost-item handling, medical emergencies, remote operator availability, and fleet management—including idling and parking logistics, charging infrastructure, public infrastructure upgrades, and safeguarding data against internal and external threats. Additionally, the complexity of full self-driving hardware—comprising numerous sensors, cameras, and high-performance computing systems—further increases maintenance demands and costs.

The profitability of robotaxis ultimately depends on effectively managing maintenance and operational challenges. Achieving this requires significant scale to offset higher costs, and it will likely be several years before robotaxis can truly compete with traditional ride-hailing services. This is especially true in the United States, where their economic viability remains uncertain. While robotaxis may help reduce traffic and pollution, they also risk displacing drivers who rely on ride-sharing platforms for their income.

The risks of AI-based FSD systems underscore the need for a measured approach to autonomous driving. While AI has advanced many fields, its limitations in autonomous driving highlight the need for a hybrid approach. In practice, machine learning should complement sensor data—using predictive models to inform, not dictate, real-time decisions—rather than an end-to-end AI approach. This should be paired with deterministic algorithms, redundant and complementary sensors, and V2X communication to deliver more consistent, predictable performance, as seen in systems like Waymo that already adopt some elements of this approach.

We still don’t have a truly transparent model that can replace the core FSD neural networks envisioned by efforts like DARPA’s Explainable AI (XAI)7. Until that becomes reality, FSD should operate within strict, understandable safety limits and clear, explainable guardrails. Ultimately, public confidence in the safety of self-driving technology is key to its successful deployment—and that depends on independent third-party validation, reproducible testing, consistent federal standards, and strong regulatory oversight.

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=10614862 Chen, C., et al. (2024). End-to-end Autonomous Driving: Challenges and Frontiers. IEEE PAMI. ↩︎

- https://news.mit.edu/2024/researchers-enhance-peripheral-vision-ai-models-0308 By Adam Zewe | MIT News ↩︎

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/interactive/2023/tesla-autopilot-crash-analysis/ The Washington Post ↩︎

- https://www.cnbc.com/2024/04/08/tesla-settles-wrongful-death-lawsuit-over-fatal-2018-autopilot-crash.html CNBC ↩︎

- https://www.autoweek.com/news/a65943782/hacker-showed-tesla-lied-court/ AUTOWEEK ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41094856/ Qian, H., et al. (2025). A Review of Multi-Sensor Fusion in Autonomous Driving. ↩︎

- https://www.darpa.mil/research/programs/explainable-artificial-intelligence DARPA ↩︎

*This article has been reviewed and edited for clarity and accuracy, with references added for support.*

3 responses to “Why AI Is Not The Solution for Autonomous Driving (FSD)”

Tube of 𝕋𝕣𝕦𝕥𝕙𝕡𝕒𝕤𝕥𝕖 ✞ Sankaran G.10 hours ago

This is absolutely unrealistic and antithetical to a timely transition. Not only do you add a tremendous amount of cost, noise, and vulnerability to the entire system, but you have a serious chicken and egg problem.

Autonomous driving needs to be completely self contained in order to be viable.

Sankaran G. Tube of 𝕋𝕣𝕦𝕥𝕙𝕡𝕒𝕤𝕥𝕖 ✞2 hours ago Implementing a hybrid approach with deterministic algorithms and communication systems does add complexity and cost. However, these costs could be offset by the potential reduction in accidents and improved traffic efficiency. It’s important to note that V2I communication doesn’t necessarily demand significant changes to existing infrastructure. Instead, it leverages the information already present in the signal infrastructure. For instance, think of a pedestrian wearing a shirt with a traffic sign pattern (hypothetically). An AI could mistakenly follow that sign. V2I technology, which we already have to some extent, can help vehicles receive accurate information directly from traffic signals, reducing the risk of such errors.

LikeLike

https://seekingalpha.com/news/4129649-robotaxi-jolt-tesla-autonomous-driving-test-goes-poorly-for-truist-securities#comment-98335573

LikeLike

[…] Why AI Is Not The Solution for Autonomous Driving (FSD) […]

LikeLike